We recently had a customer come to us to say their account had been hacked, and spam email was being sent from our system. We immediately investigated but were unable to find any sign of problems. The customer insisted the emails they had received were coming from our system because the “From” address was their email marketing address. In fact, their account hadn’t been hacked at all. It was just another example of scammers taking advantage of the “Friendly From” name in an attempt to fool readers into thinking an email was from someone else.

We’ve all received those emails that claim to have been sent by WalMart, Chase Bank, FedEx, and others. They’re annoying enough already, but they become intolerable when the company being spoofed is your own.

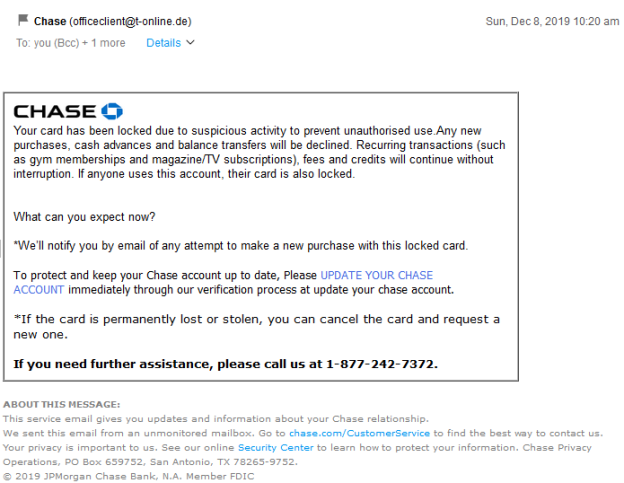

Scammers will copy the identifying elements from a sender’s mailings, such as the design and logo, in an attempt to convince readers that the email came from the legitimate company. But how can you recognize this, and what can be done about it?

Prevention

When email was created in the early 1970s, the designers had no idea how popular it would become or the range of problems that could be introduced. They created a simple, flexible system that allowed email to become what it is today, but that flexibility also enables malicious people to abuse the system. Email allows you to assign the “from” address to anyone you want. This is useful, especially for marketers who want to use an ESP to send emails that appear to have come from their company, but it can also be used to prey on a good company’s reputation.

To help prevent this kind of abuse, you need to add the email authentication protocol SPF. This protocol tells the receiving mail server which mail servers are allowed to send email using the “from” domain, so should reject email that is being sent by some other entity. The use of this protocol will help prevent phishing emails (those pretending to be from eBay, Bank of America or other brands with good reputations) from landing in your inbox. It is important that your SPF specification end with a “-ALL”, rather than “~ALL” or other options. The dash indicates that the email should be rejected, which is what you want.1

DKIM (pronounced “dee-kim”) is also a popular email authentication protocol. DKIM uses encryption to verify that an email message was sent from an authorized mail server. A private domain key is added to the headers on messages sent from your domain. A matching public key is added to the Domain Name System (DNS) record for your domain. Email servers that get messages from your domain use the public key to decrypt message headers and verify the message source.

An email authentication protocol popular with high-profile, brand-driven companies is DMARC It was created by PayPal with the specific intention of preventing spoofing and phishing, and is most useful for companies that are often targets of these types of scams. For most businesses, SPF and DKIM should do the trick. DMARC only works if you’ve set up both SPF and DKIM.

Recognition

So what if someone contacts your organization saying they have an email from your company that is spam. How can you determine if your ESP has been hacked or if someone is sending email using your company name as a “from” address?

The content is seldom useful. Any decent ESP allows customization of the content, so any link could be sent and the unsubscribe information can be specific to you. These can be faked by the malicious entity.

In many cases, these attempts to trick readers into thinking an email comes from a legitimate source are easy to spot:

Although this appears, on the most casual glance, to have come from Chase Bank, there are giveaways that it did not. The most obvious one is that the actual email address is not from Chase, but from a free email service in Germany. Clearly, a major institution like Chase Bank is unlikely to use a free email address to send out information about a customer’s account status. Presumably, upon clicking the link, you’ll be taken to what looks like a sign-in page for Chase. They’re hoping you will continue believing the ruse and enter your login name and password.

If you want to find out where an email came from the email headers are your best source of information. Unfortunately, email clients don’t always make viewing the headers easy. The desktop version of Outlook, for instance, requires you to go to the File menu and choose Properties, then the headers appear in a small scrolling box that can’t be resized.

Yet, here too, though the headers are useful, they can be faked as well. Under the covers, headers are just part of the email content, and the malicious entity can provide any headers they want to the email. However, the standard rules for email are that the mail server that accepts and email should add some “received” headers. Your mail server knows the IP address of the mail server that is sending the email and should provide this information, as well as the name associated with that IP address, as part of the “received” header.

Often there will be multiple “received” headers. The email protocols were originally designed to be store-and-forward systems where an email might require passing through several mail servers before getting to the one that has the proper mailbox. In our modern environment multiple “received” headers often come as part of the sending process. Many ESPs and other senders will generate the email on one computer that relays it to another computer for actual delivery. This will result in multiple “received” headers that can be used to trace the path back to the original sending computer. The standard for “received” headers is to add from the top, so the data near the beginning of the headers data should be the data added by your mail server and can be trusted. Everything after that is suspect.

Understanding “received” headers can be a bit tricky, so you may need to ask your ESP or email expert for help. But simply scanning the data added by your mail server can often give you a clue of where the email came from. If the headers say “Received: from mail-ot1-f48.google.com ([209.85.210.48])” for example, it should mean that your mail server received an email from IP address 209.85.210.48, which, when looked up, inform us that it is a Google mail server. If the malicious email says it is coming “from” your brand, but the headers say: “Received: From h2hclan.com ([36.89.36.149])” you can feel confident it was not your ESP that sent this email.

Finding the Headers

If a client, co-worker, neighbor, or whoever forwards you an email that claims to be “from” you, the important headers will be lost. A forward is actually a new email message, with a new set of headers, and the content copied from the source email. This email will not show you the interesting header information. To get that you need a copy of the email as it was received. With most email clients, if you create a new email message and include the problem email as an attachment, the headers will be retained. The trick is getting that person who received the malicious email to send you the email as an attachment.

Conclusion

If you have a popular brand, and especially if you have good email deliverability, malicious people will eventually decide to try and take advantage of all your hard work to deliver their junk. The only thing you can do about this is to have the proper SPF records in place, which will limit the damage. Being able to recognize when an email has been sent faking your domain is important so you can quickly determine if someone has gotten into your email server or ESP, or if it is the more likely case of someone attempting to abuse your good reputation with an email pretending to be “from” your company.

1. Fortunately, our customer had the proper SPF records in place, so the damage was minimal. It seems that more North American mail servers pay attention to SPF records, and not so much in China and Asian countries where this particular abuse-email was targeted.

© Goolara, LLC, 2020. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Goolara, LLC and the Goolara Blog with appropriate and specific directions (i.e., links) to the original content.